Interview on the EU: “Alone in the world”

23 Jun 2025

Why the European Union is struggling to position itself geopolitically in a time of global crises: interview with LMU law professor Ulrich Haltern.

23 Jun 2025

Why the European Union is struggling to position itself geopolitically in a time of global crises: interview with LMU law professor Ulrich Haltern.

Ulrich Haltern is Chair of Public Law, European Union Law, and Philosophy of Law at LMU. In our interview, he explains how utopia became reality in the course of European integration, and describes the challenges the European Union faces because not the Union, but its member states are considered citizens’ political home.

© IMAGO / biky

What contribution can the EU make to greater peace in the world? After all, it was founded with the goal of securing peace.

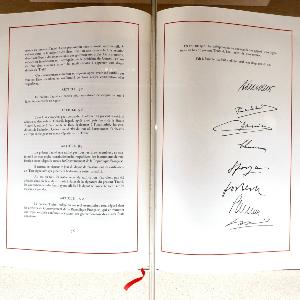

Ulrich Haltern: European integration started out as a peace project between the member states, and it has been extremely successful. The Schuman Declaration of 1950 – the foundational document of European integration – was written as a response to the antagonism between France and Germany. Its objective was to place coal and steel under shared control, so that war between France and Germany would become not only materially impossible, but also unthinkable. 75 years ago, rendering war unthinkable seemed utopian while redering war materially impossible seemed realistic. Today, it’s the other way round: War is always materially possible, but between Germany and France, and within the entire Union, it has become unthinkable. Utopia is reality. However, this success stops at the Union’s external border. For all the internal strength of the peace project, externally it is weak.

Why is that?

The EU’s foreign and security policy has often been feeble, at times embarrassingly so. It is unfair to blame the Union though: it is the member states who jealously guard their foreign policy powers, refuse to cede most of them to the Union, and deny the Union a major role in this arena. The Union therefore lacks competence and a single voice in foreign relations, and if it was able to find a single voice it had to rely on soft power. Soft power, however, is not in great demand at the moment, when maps are redrawn, armies deployed, and trade relations used to divide and conquer.

The EU is not a state; rather, it inhabits the crevices between states.Ulrich Haltern, Chair of Public Law, European Union Law, and Philosophy of Law at LMU

In a recent interview in DIE ZEIT, you said that “Europe has an empty soul and a cold heart.” Why do you see the EU like this?

This is the flipside of the same process that has brought the EU such success. The Union and its member states are two different forms of political community which command two very different imaginations. Legally, states do not defer to other internal or external authority. Politically, states wield constitutional power residing in “We the People”. Culturally, states are characterized by primary political identity. They are able to elicit deep political loyalties. In return, citizens not only receive protection and security, but also something like a political home. They know who they are.

The Union exhibits none of these attributes in law, politics, and culture. Legally, the EU is limited to the powers granted to it by its member states. Politically, it lacks pouvoir constituant. And culturally, it lacks a primary political identity. It is not a state; rather, it inhabits the crevices between states. That’s a crowded space where many competing demands meet and where effective action is extremely difficult. Moreover, European integration is strongly driven by market integration. The internal market is at the heart of integration, it is a veritable prosperity machine. However, markets cannot tell us who we are. They operate through desires, which are mere placeholders. Markets and money are indifferent to history and individuality. Without these two, no identity can emerge. This places the EU at the thinner end of the scale of political community.

Of course, European integration was a resounding success for precisely this reason. After World War II, states needed to work around the frictions and the conflicts of a hyper-political nationalist past. Turning from the imagination of sovereignty to the imagination of the market was the perfect tool. Borders lose their existential meaning, and Europe was able to dream of a post-sovereign, perhaps post-political community. Political imagination stopped being rooted in the soil, and instead became as fluid as money flows in a world of trade, travel, and consumption. Rather than looking to the past, Europe looked to the future. A brilliant strategy.

That strategy becomes a problem, however, once integration goes deeper than the market and requires political decisions that derive their legitimacy from political identity. One such area is security and defense policy. For the first time since the World War II, Europe stands pretty alone in the world. We’re losing the United States as a reliable partner, and other global players are not close allies. The global order, as we know it, is no longer holding – the “West” is dissipating. People seem to expect the Union to occupy that vacant space. Indeed, if EU member states want to continue to play a role on the world stage, and have a seat at the table when power is redistributed and the rules are rewritten, they need to deepen and broaden European unity.

Indeed, if EU member states want to continue to play a role on the world stage, and have a seat at the table when power is redistributed and the rules are rewritten, they need to deepen and broaden European unity.Ulrich Haltern, Chair of Public Law, European Union Law, and Philosophy of Law at LMU

Is this lack of political identity the reason why the EU is struggling to respond to current world events?

It is part of the problem. Political identity is the hallmark of a deep political community. In such a community, it becomes possible to engage in long-term strategic thinking while also fusing trade, investment, defense, and politics into a coherent strategy. You become able to join and align the three elements of geopolitics – power, territory, and narrative. All three have been alien to the EU. Power is located primarily in the member states. Territory has always been volatile in the Union, with its enlargement rounds, Brexit, and its member state controlling many aspects of territorial policy. And a shared European narrative has never been able to hold its own against competing member state narratives.

The Union cannot simply fill these gaps from one day to the next. Community is not just a matter of common interest and rational benefits, but also of belief – ‘imagined communities’ is the phrase political theorists like to use. We do not reason ourselves to belief. The road to belief is not paved with strong arguments.

We have seen the consequences time and again in the course of European integration across all policy areas. When we made progress at the European level in a way that was entirely reasonable as well as in the long-term interest of all member states – progress, that is, that made European government more effective and helped advance member state interests as well –, that progress became, at the same time, the source of deep unease and discontents at the member state level. The reason is that European effectiveness and national self-government seem pitted against each other. Deep integration has therefore always been received with considerable ambivalence.

Take, for example, the mode the Council of Ministers (the Union’s major legislative institution) makes decisions. Originally, these decisions had to be unanimous. Accordingly, every member state had a veto and controlled 100 percent of the resulting legislation. As the number of members continued to grow, unanimity became less and less effective, up to a point where the Council was blocked. Member states therefore introduced majority voting, first for a few areas and then for more and more of them. Of course, this is much more efficient, but it creates situations where member states are outvoted and stuck with laws they do not want.

Majority voting is a matter of course in a democracy. But democracy is premised on a wide set of conditions and requirements. One of them is that the political community shares an understanding of “We the People”. The Union, however, is a community in which we continue to identify, in the first place, as Poles and Germans, Italians and French, Portuguese and Croats. Being outvoted might come to mean that some feel as if it is the “others” who determine the way I am supposed to live, and that my primary political community has ceased to govern itself. That appears hyperbolic, and yet it is precisely this sentiment that led to Brexit. It’s a profound democratic problem, and also a problem of political identity.

But with 27 member states, unanimous decisions are not always feasible.

You´re absolutely right. European heterogeneity is breathtaking. Some member states have external borders, others do not; some have the Euro, others do not; some are big, others are small; some are rich, others are poor; east versus west, north versus south, agricultural versus industrial. It’s incredibly difficult to find a common denominator, and to reach solutions acceptable to all. Indeed, it’s a testament to the EU’s resilience that it has managed to do exactly that, in spite of its growing membership from six to 27 states. But resilience does have its limits – there used to be not 27, but 28 members. One such limit is what we talked about: the feeling of being governed not by ourselves, but by others. It originates from the trivial fact that the EU is not a state and does not project popular sovereignty. It projects many contending objects of representation: in the Union, representation functions like a prism.

I think citizens do identify with the Union, just in a different way than they do with their member states. Identification with the Union will not produce a primary political identity that is European.Ulrich Haltern, Chair of Public Law, European Union Law, and Philosophy of Law at LMU

The EU flag shows a circle of twelve stars, symbolizing the values of unity, solidarity and harmony between the peoples of Europe. | © IMAGO / Bihlmayerfotografie

Should the EU be doing more so that its citizens identify with it?

I think citizens do identify with the Union, just in a different way than they do with their member states. Identification with the Union will not produce a primary political identity that is European. The surveys that the European Commission regularly commissions always return the same answer: Citizens locate their primary identity in their respective home state.

The EU is indeed attempting to create a shared European identity, and most member states support that effort. To this end, they reach deep into the box of tricks of state heraldry. They pull out a hymn, say, and a flag with 12 stars, and try to infuse them with symbolic meaning. None of this is convincing, there’s always something wooden about these symbols. They lack authenticity. Little wonder: you cannot simply engineer beliefs about belonging and loyalty.

There are exceptions. When Ukraine was attacked by Russia, Ukrainians raised European flags. The flag, at that point, had a distinct meaning and stood for something. But even then, this “something” was still not a primary European identity.

What has happened in the EU’s security and defense policy since Russia’s attack on Ukraine? Have there been changes?

Yes, many. The Common Foreign and Security Policy is increasingly being overshadowed by the Common Security and Defence Policy, specifically in the area of defence. There have already been several legislative acts and many further proposals for strengthening European defence capabilities. The goal is to create greater independence from the United States and promote common procurement projects. To further this goal, the EU provides new financial instruments and establishes a network of partners beyond member states: the United Kingdom, naturally enough, but also the EFTA states, Ukraine, accession candidates, and security partners like Japan and South Korea.

Does this mean we’re taking the route of closer economic cooperation again?

Yes we are, to a good extent in any case: strengthen defence industry, allow for easy financing etc. No surprise there; after all, this is the core function of the Union. Removing inefficiencies, creating a large European market – it’s what the union has been doing since 1952, and there is a large consensus about it. That’s why it works so well. Economic cooperation has always been the European recipe for success, and now we’re hoping it will also apply to defence. The weapons market was previously shaped by security (read: national) policy, and thus highly fragmented. Naturally, this will not work nearly so well when we talk truly military capabilities. Military capabilities rely on clear political leadership and a unitary command structure. This is scarcely feasible within the European Union.

Do you see strategies being developed to change things here?

Something like this requires either sweeping, compelling political momentum or else a lot of time spent on incrementally networking military capacities. We don’t have much time, if we believe the defense experts, and the current political impulse doesn’t seem to be all that compelling either. It will presumably be a mish-mash, with the stronger and willing member states trying to get the smaller ones on board while also establishing a new security architecture with further partners like the UK, EFTA members and accession candidates.

Compared to international law, the EU inhabits a different universe, especially with regard to the binding nature and enforcement of its decisions.Ulrich Haltern, Chair of Public Law, European Union Law, and Philosophy of Law at LMU

teaches European and international law. “Many of my students choose to study these subjects for idealistic reasons. It’s depressing to have to explain to them that the weakness of international law is part of the reason why the world is so bloody. I am trying to take a positive tack and motivate them to find ways of strengthening it.” | © Martin Henze

How does the EU with its various problems compare with other international organizations and international treaties?

Compared to international law, the EU inhabits a different universe, especially with regard to the binding nature and enforcement of its decisions. International law is a legal framework with a flat hierarchy. States create the rules, and they are also the ones bound by them and responsible for enforcing them. That makes it easy for them to weaken the force of law, by either not consenting or by preventing enforcement. Non-compliance is relatively easy and cheap. We see this all the time, and it is clearly getting worse. Sometimes I wonder if there even is international “law” worth the name.

The European Union is blessed with a Court that, since the 1960s, has fashioned a legal enforcement system akin to that of nation-states. Member states cannot easily veto rules, and they cannot prevent the enforcement of EU law against themselves without serious consequences. Compliance is very high. However, this legal system, which is reminiscent of municipal law, is limited to certain policy areas. It does not cover defence, foreign, and security policy. If the European Union is to play a geopolitical role, that would have to change. However, this is precisely where we encounter the great, almost tragic dilemma at the heart of integration: Effectiveness and self-determination are traded off against each other. On the one hand, we want to remain a world player; effectiveness therefore demands deeper integration. On the other hand, defence is different from removing trade barriers in a market. Do Germans or Poles really want 26 other states, the European Parliament, and the Commission (an independent executive EU body) allow a say in deciding whether they send their young men and women to kill and die? It seems this is a decision “we”, the political community that commands our loyalty and that forms our political identity, should make for itself. Practically, this dilemma leads almost certainly to ambivalence and dashed expectations.

Yet these expectations are also a sign that the EU is becoming increasingly important in the lives of citizens. Everybody looks to Brussels when it’s about geopolitics. If you want a silver lining, this is it.

Ulrich Haltern is Chair of Public Law, European Union Law, and Philosophy of Law at LMU Munich. Two books of his have appeared this year: Verschlungene Staaten. Die paradoxe Mechanik der europäischen Integration“ (Verlag C.H. Beck) and The Constitution of the European Union (Hart Publishing, an imprint of Bloomsbury).